Gegenschein is usually a science fiction fanzine, with book reviews and reports on convention trips. Next issue will revert to the more usual material. This issue I wanted to mostly cover the death of my mother, while events are still in my mind. I've left out the names of neighbours, hospital staff and so on for privacy reasons. SF fans are mentioned by name, as is traditional.

A Death in the Family

Hospital Visits

Ella-Tinka

Clean Up

Sell Out

Phoebe Edith Lindsay

Ancestors

Crushing Blows

I wrote the above paragraph in early January. On Monday 13th January my mother suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, and died on Friday the 17th without regaining consciousness.

Those who would rather not know the details could skip to the next item, or stop reading now. With minor exceptions such as Sell Out, and Crushing Blows, the entire issue relates to the one event.

There was no reply from my mother's house when I phoned, but I knew she had intended to go shopping in Penrith on the Monday morning. She had always been more of a shopper than I am, visiting Penrith more in a fortnight than I do in a year. However as was often the case, I had seen her for lunch on Sunday, and she had seemed fine then.

A neighbour who visited on the Sunday afternoon told me later that she thought my mother's speech was a little slurred. It would not have surprised me to find that she had ignored any preliminary signs. It had happened before, with my mother denying any problem. And I admit to taking precisely the same attitude towards medical intervention myself; I haven't seen a doctor (except socially) in many years.

The garage next to the bus stop confirmed an ambulance had taken someone away, but they didn't know the details. The local general store was nearby, and they confirmed that the ambulance had been called from there, and that it was for my mother.

An intending passenger for the bus had discovered my mother slumped on the seat at the bus stop. She apparently had worked in the medical area before retiring, and took my mother's pulse, and immediately called an ambulance. None of these attending knew how to contact me, but they certainly did all the right things for my mother.

There seemed to only be an emergency number for the ambulance, no local number for their site in nearby Springwood, which was somewhat frustrating. I figured they would have gone to the large public hospital near Penrith, some 30 kilometres away.

Nepean Hospital quickly confirmed they had my mother, and put me on to a doctor in the emergency room. He told me she had either a cerebral hemorrhage or a stroke, and was on a respirator, that they were still doing tests. He also told me it was unlikely that she would recover.

After phoning Jean with the details, and trying to contact some of my mother's friends and neighbours, I took the train to Penrith. I couldn't recall ever visiting the hospital (I've only lived here 30 years after all), so I caught a taxi. Just as well, as it would have been at least a 40 minute walk.

My mother had been taken to surgery while I was travelling. The emergency room doctor saw me in a private waiting room, confirmed that it was a cerebral hemorrhage, and told me there was little hope. I got the impression that, had they known my mother was 83 years old, they would have restricted treatment to drugs rather than attempt surgery. Since she had been found in circumstances that showed she was living independently, they may have assumed she was somewhat younger.

Somewhat later I was shown to the Intensive Care waiting room, where I waited a seemingly endless time. Finally got in to see my mother late that afternoon. She was on a respirator, not breathing for herself, looking very small and fragile, and not showing any response to anything. The intensive care staff also didn't expect her to last long.

Jean collected me at the hospital, and we drove to my mother's place, collected her cat, and gave her neighbours the news. I phoned as many of her friends as I could identify, but there didn't seem to be any master list to which I could refer. I was to spend each evening I went to her place looking for names and contact details for her friends. Luckily, many of these people also spread the word.

I visited the hospital each day, sometimes twice a day, without any change. The people at work were (as always) very good about me taking off without notice. I did go into work for a few hours on the Wednesday, partly because it helped take my mind off the situation. Same on the Thursday and Friday.

An EEG machine didn't show any pattern consistent with recovery or any conscious brain activity. On Wednesday the respirator was removed, after the doctor consulted me. The nurses obviously expected the end to be soon. Didn't happen, and I finally went home. The oxygen feed was also gradually reduced over the next day until she was breathing normal air. Still no change. They moved her from the Intensive Care ward to a ward not equipped with respirators, but sharing other facilities with ICU. The nurses were very kind and thoughtful throughout. I guess not having any personal involvement with patients would help, but I don't think I would want to do their sort of job.

On one of the days the hospital administration suggested I take her belongings back home. She had what I thought was an excessive amount of cash in her bag, so the hospital had put that in their cashier's safe. They also asked me to sign some paperwork on the Wednesday, just two forms. Since my mother was a repatriation pensioner, there were no actual bills for me to see. In particular, the image often given in the media of impersonal bureaucratic forces sweeping aside compassion just did not seem the case. There was only the one brief signing of papers, days after treatment started.

I did find the waiting a strain. In most situations you are able to take some action (whether that is effective or not), but here you could only sit and wait.

On the Friday she was not obviously any worse than previously. Jean had loaned me her cellular phone for the week. After leaving the hospital I walked back to Penrith (about 40 minutes), and was nearly to the station when the nurse phoned with the news. I stopped at the funeral director near the station, and signed the papers. I took a taxi back to the hospital to view the body. That wasn't something required, but I felt it was necessary for me at least. It seems strange how different a body is when life has left it. Although I had really come to terms with the situation over the five days, and already regarded myself as having lost her, it didn't really seem final until I saw the body.

I spent the evening, and that weekend, contacting as many of her friends, relatives and neighbours as I could, and wrote a bunch of letters setting out the funeral arrangements. I'd arranged that for the mid morning Thursday, to maximise the chance of letting more of her friends know. Although she had not been to church for many years, I'd also contacted a local minister. Jean dropped off the notes I'd prepared for him, and later I visited to talk with him about the ceremony.

The funeral was relatively brief, with about thirty attending. I'd arranged it at the funeral home chapel, as that was very close to the railway station. I believed her friends would mostly not have cars, and would need easy access by public access, and that proved generally correct. One factor I hadn't considered was that some would be visiting the local hospital, and would need to take into account visiting hours.

After the funeral I'd arranged a table at a small cafe in the local mall a street away. About a dozen people came to this, so I was able to talk at greater length with some of them. I hadn't known who to expect, so it was good to have this chance to see my mother's friends, some perhaps for the last time. Although all said they wouldn't eat anything, when the cakes and pastries arrived, they were indeed eaten. I remember my mother needed to eat at regular times to help control her diabetes, so I was pleased no-one was left hungry. On the basis of my own feelings, I'd suggest the idea of a wake is a good one. Throw a party, and perhaps everyone will feel a little less sad.

The ashes will be interned at the small cemetary at Faulconbridge, near where she lived for the past 30 years. I was unable to have them close to an azalea, as I had originally wished, but I hope the present site appropriate.

My mother was living an independent life right up to the end. We had discussed nursing homes and the like. She would not have fared well in even the best run of them. She wouldn't have been able to keep a pet. Often, even a little help, like the community shopping bus, is enough to let a person continue to live at home. I am glad she managed to live the way she wished until the end, and hope it is the same with me.

Shortly after becoming settled in, Tinka managed to find her way onto the roof, without actually finding out how to get down again. A little later she learned how to get out the window, into a tree, and down. Due to the way the windows open, she was not able to get back in again, leading to meowing outside the window at night. She also knows how to jump off things that are too high for her, and then when she hurts her paws, she complains. Real Soon Now we will train her to use the cat door ... the same cat door that Minou resisted using for six months. Oh joy!

Jean and I had forgotten how energetic young cats can be. Tinka is a very disruptive influence on the house.

I knew my mother had an excess of food in the fridges, as I'd sometimes offered to help clean them out. I didn't realise that I'd be throwing out three 240 litre big bins of food that had passed its use-by date every garbage night for the next three weeks. I didn't even manage to empty the freezer compartments in the first week.

Jean and I took shoes to the charity bin. Something like ten large bags of shoes. Over thirty bags of clothes. There was an incredible quantity of dressmaking material, filling cupboard after cupboard. At least two car loads. Plastic bags, all neatly organised, to fill two giant boxes. Seals from bread bags, filling two four litre bottles. Three four litre ice cream containers full of soap. Cleaning supplies of indeterminate vintage. Thirty boxes of gift pack talcum powder, various brands and ages. Every Xmas card received for the past few decades.

There were old model appliances, still in their original boxes. Indeed, almost every appliance still had original boxes and manuals. Three sewing machines, two knitting machines. Cook books, natural history and gardening books. Historical society monographs. My school books from high school, my high school yearbook. A clockwork Hornby train set I didn't recall. Toys I did recall, filling an entire box. A clock I had as a kid. Indeed, about a dozen or so clocks in all.

After giving away or throwing out things for close to three months, we finally have my mother's house mostly down to furniture and crockery. I'm going to have a local auction place attempt to sell off what remains, if they think there is sufficient value in the house contents to make it worth their while. Some of the stuff that I think is junk might be otherwise; there was an old trunk, lined with newspapers ... from 1871. Who knows what warms the hearts of collectors - probably stuff I've already thrown away.

While emptying my mother's home, and comparing it with my own cluttered home, I couldn't help but realise where my own tendencies as an accumulator of kipple were leading me. I could see myself ending with mounds of kipple spread throughout storage facilities around the city, slowly decaying into utter rubbish, not unlike another collector I know. It seems unlikely I would actually lack comfortable living space because of the collection, as I'm not that far gone in my accumulating, but it could perhaps happen.

My mother accumulated things for thirty years. She must have found them of value or comfort. I couldn't see what there was in it of sufficient value to even try to sell it. I rather think anyone looking at my house might well come to the same conclusion. I no longer believe this situation acceptable.

I'm now emptying my house of the accumulated clutter of a lifetime. Underused consumer goods are going to my mother's house for the auction. Excess furniture is going. Old musical records, record player, and all that sort of stuff. Stacks of paper products. Over the next year, I'm culling my book and fanzine collections even more.

When I get things to the point where the floor no longer looks like a midden heap of history, I'll start thinking on hard decisions about what else I can get rid of.

(9 August 1913 - 17 January 1997)

An expanded and corrected version of material I provided to the minister for my mother's funeral. In particular, I added exact dates and genealogical details where I know them.

Edith Harper (my mother) was born at South Sydney Woman's Hospital, Newtown, on 9th August 1913.

In 1913, Canberra was named Capital City of Australia. Grand Central Station opened in New York, and the Panama Canal opened. Typhus vaccine is discovered. The Australian basic wage increased to eight shillings a week. The population of Australia was 4,893,741. Charlie Chaplin makes his film debut.

Her parents, William George Harper, a storeman, born in England, and Bertrude Harper (grandmother) (formerly Bertrude Phillips, of Eveleigh, Sydney) married on 6th March 1907, and resided at Blacktown, some 40 kilometres west of Sydney, in those days full of market gardens and bushland.

For much of her childhood Edith lived in the Mascot and Zetland area. As a result, she had little contact with her older brother, Edward George Harper (who married Sybil, and died 20 January 1987) or younger brother Gordon Harper. I believe she lived with Charlotte Wilkins (Wright), an older sister of her grandmother, Eliza Harper (Wright).

She could remember bullock teams pulling wagons through the mud of Bourke Street. She recalled the Clancy brothers building a wooden aeroplane in their garage, and planning to fly it from the golf course. When she finally took a flight to England, she could hardly help but comment on the contrast between what she had seen as she grew up, and what existed then.

As with many of her generation, she remembered the Depression, and banks closing. She never did entirely trust banks again, although she was later to work briefly in one. I found an old Government Bank account of her father's from the 1930s in her papers, and remember her telling me of the days in which that bank closed. For most of this period she was a machinist, dressmaker and seamstress. She continued to make clothes for herself, and as presents, for much of her life.

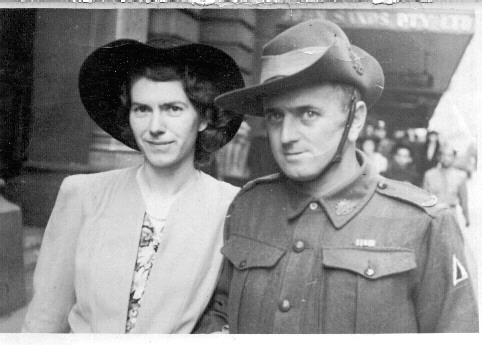

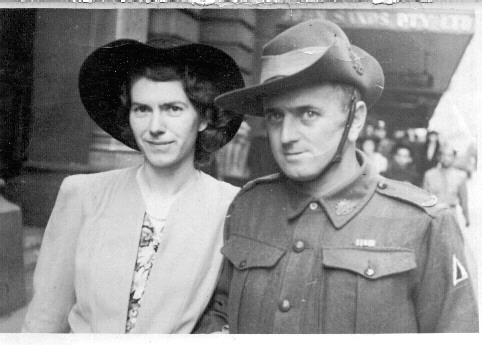

During World War II, on 15th July 1944, she married a soldier, Bruce

William Lindsay, at the Beckerham(?) Memorial Congregational Church at

Mascot with Minister Sydney Samuel Walter Horner doing the marriage. The

witnesses were M E Lindsay and R A Lindsay, and I assume these were Rob

and Marjorie, brother and sister to Bruce Lindsay.

Bruce Lindsay (my father) was born on 2nd February 1913 at Berry Street, Mascot. His parents were William Garson Lindsay, variously listed as an Engine Fitter of Balmain, or as a farmer, deceased prior to this marriage, and Eva Lizzie Whiting (grandmother), of Alexandria.

Bruce Lindsay's normal occupation was listed as a bus conductor. They lived at Zetland, a few miles from the centre of the city, near what was then the Nuffield factory. There was one child, me, born on 2nd February 1947. On 31st May 1952, Bruce Lindsay died of war related illness at Concord Repatriation Hospital.

Edith worked in a variety of jobs in the Zetland area after her husband died. I recall being taken with her to work at a local bank, before I was old enough to attend school. As a result, I could use a typewriter (badly) before I could use a pencil.

She worked for the Rev. J. W. Spencer at Newtown Methodist Mission in King Street for many years, assisting in the day to day working of the Mission.

Edith moved from Zetland to Hurstville in 1959, into a house she had had built, but always wanted to move to a more natural setting, outside the suburbs. She was assisted by the Methodist Property Trust in obtaining the mortgage. She mentioned at times the problems women had in obtaining a bank loan in those days.

In 1964 she had her final home built at Faulconbridge, by local builder George Cochrane, largely to her own design.

She was particularly proud of managing to grow a variety of native plants, including a large number of native orchids, although in her later life the yard proved too much for her to manage.

She was a member of the Springwood Historical Society, and of the Springwood Music Society. In her later years she was more reluctant to attend evening events, as she found a normal day of activity more and more tiring, especially as she never really grew out of the habit of arising with the sun.

Edith rarely saw doctors, however when she was diagnosed as diabetic, nearly a decade ago, she finally was persuaded to carefully follow their directions on diet and exercise. This produced such an immediate improvement in her health that she was able to attend more events for several years.

Edith often mentioned how much she enjoyed using the weekly Blue Mountains Community Transport bus for shopping and other activities. She often claimed it was what made it possible for people such as herself to stay independent in their own home.

A few years ago she was somehow persuaded to take care of a young, very scared black cat she named Ela-Tinka. The cat grew considerably larger under her care, and indeed was probably more than a little overactive for someone in her 80's. She joined the NSW Animal Welfare League to ensure that the cat was well cared for when she could no longer do so. The cat is now being looked after by Jean and I.

Eliza Wright appears to have been one of 12 children in her family. I also know of a Jane Wright, born 21st May 1867 in Horstead. Another older sister, Charlotte Wright, was born 10th March 1860 in Horstead, Sprowston, Norfolk. The parents were George Wright, a farm labourer and Elizabeth Wright, formerly Abel. The mother made her mark, rather than signing the birth certificate. Charlotte was baptised on 22nd June 1862. On 26th June 1880, Charlotte Wright married George Wilkins, a illiterate labourer of North Walshaur, Norfolk. The marriage certificate lists William Wilkins as the father of George Wilkins, and lists George Wright as the father of Charlotte Wright. The witnesses were listed as Thomas Wilkins (also illiterate) and Lydia Wright.

Charlotte must have moved to Australia about three years after her marriage. She died on 28th May 1948 at 406 Elizabeth Street, Zetland, in the house where my parents lived and where I grew up. There are a number of errors in the death certificate. Her mother is listed as Martha Able, where I believe it should be Elizabeth Abel. No children are listed on the death certificate. I was too young to remember her, however I do recall an old man in the house, and wonder if that could possibly have been George Wilkins?

Charlotte's husband, George Arthur Wilkins, was born on 3rd November 1859 at Whitehorse Common, North Walsham, to William Wilkins, an agricultural labourer, and Charlotte Wilkins, formerly Turner.

My wooden balcony at the back was damaged beyond repair, with the timbers splintered by hail. My shed was damaged, but it had previously had a tree fall on it, so the extra damage wasn't worth worrying about. I appear to have lost a lot of the garden, including many plants that I've had a decade or more. Our trees are evergreens, and don't normally end up stripped of their leaves.

Local newspaper reports next week indicated many homes damaged, with home extensions and part of the roof of the local high school crushed by the weight of ice. I mean, ice! In December? In Australia. Normally the only ice here is in my drink, and that is usually melting too fast!

Due to the heavy ... social season ... around Xmas, I didn't hear of the storm when it happened. I didn't discover the damage until I returned home (long after midnight, and not precisely sober) on Friday two days after it happened, and discovered my floor coverings were pretending to be a swamp. Dragging them downstairs and outside was not the most pleasant prospect at that hour. Jean kindly came up on Saturday and helped me clean up. After the house was slightly less untidy, we looked at the yard, covered in leaves. Over 40 garbage bags of leaves were collected from my small yard, enough to completely fill a VW van. And there were still leaves all over, including inside the house, when the weekend ended.

I had absolutely no luck in phoning any skylight, roofing, tiling or general repair people all Saturday. Phones went unanswered, mobiles were switched off. I thought my plastic and duct tape patches would be severely tested over the next week, when at least some rain was forecast. Even the "24 hour" insurance number didn't open until nearly 9 a.m. It seemed everyone who did any sort of repairs was already fully booked.

On Sunday I wandered over to the home of the builder who had repaired my roof and rebuilt my front balcony previously. He and his helper were drinking homebrew beer on the front verandah, and regaled me with tales of damage around the district. They came over on the Sunday afternoon and put up tarps, and gave me a quote on repairs. At least I didn't get any more damage when it rained.

Jean kindly drove up to my place to meet the insurance assessor one afternoon while I was at work. It is at times like this that I do actually somewhat regret not owning a car. During the week I managed to get some substitutes for the skylight tiles delivered. They were not nearly as well made as the originals, but there was no chance of getting the correct ones for weeks. On the Sunday before Xmas and on Boxing Day, the builder came over and completed repairs, or I'd still have three rooms open to the sky. Necessary repairs so far have cost me $2000, but are mostly complete. The insurance eventually sent me some money to cover it, and didn't complain about the bill.

During repairs, the vibration from demolishing the balcony encouraged

shelves to leap from the bookcase, so I had an eight metre long bookcase

with 2400 scifi books self destruct in front of me. I usually have a

few books on the floor, but this was really ridiculous. I nearly got

pulped. Jean had said she thought the bookcase was looming over her

more than usual, and I thought she was imagining it. She will never let

me live that down.