It Goes On The Shelf

No.1 April 1985

Published at The Sign of the Purple Mouth by Ned Brooks4817 Dean Lane, Lilburn GA 30047-4720

nedbrooks@sprynet.com

Website - http://home.sprynet.com/~nedbrooks/home.htm

Cover art collage by editor, sources lost

May Ghu bless this fanzine and make it worthy at least of the sacrifice of the trees that died to produce the paper. If you don't like the artwork - or even if you do - send something better, as Your Humble Editor is severely lacking in artistic ability. Preference is for line art that will Xerox well for thermal mimeo.

Ratings:

91-100 - Steal it if you have to!

81-90 - Worth Looking for

71-80 - Wait until it's remaindered....

61-70 - For collectors only.

51-60 - For completists only.

11-50 - Forget it!

0-10 - To read aloud in the con-suite at midnight....

Note: Alas, this is not on my shelf - even Goldstone and Sweetser, who did the definitive Machen bibliography, never saw a copy. There were only ten copies made! On the following pages, however is the title essay, as recovered from microfilm of the 1931 Dalton Citizen, where it first appeared.

Mr. Agate, one of our most distinguished literary and dramatic critics, said a very striking and arresting thing a few weeks ago. He was reviewing a book, the author of which had declared that in his opinion, great music, the music of Mozart and Beethoven, was the very climax of civilisation: in itself civilisation, and the pure essence and expression of civilisation.

Mr. Agate would have none of it. He swept music aside, and with it architecture, sculpture, painting, all the arts; including, I suppose, literature, though I don't think literature was expressly mentioned. "None of these things," he said, "counts. When I speak of civilisation, I mean good sewage."

Let us not endeavor to score off Mr. Agate, as we say, referring to that sacred British institution, cricket. Let us not get gay with him, as I believe you say in America. It would be very simple to ask Mr. Agate why, holding that good drains make good men, he passed his days in judging plays and books; matters, according to his doctrine, of no consequence whatever. I suppose his answer would be: "Because I want to earn a lot of money, so that I can afford to live in a house where the sanitation is perfect; and so I give in to human folly."

But we will not cross-question Mr. Agate; there is always something unmannerly, almost brutal about the argumentum ad hominem, the confronting a man with the consequences of his own opinions. I have quoted this saying about sewage, because I believe it to be a survival, because I believe that it is the utterance of a doctrine now dying, soon to be dead.

With a kind of brusque and biting humor, no doubt, Mr. Agate intended to signify that he was a utilitarian and a materialist; a believer in the school of Jeremy Bentham, of the elder Mill, of the sect known as the Philosophic Radicals, who uttered their voices in parliament as Bright and Cobden, who are expressed in literature by Mr. Gradgrind, the Hard Fact man. The sect spoke in a leading article in The Times, when William IV was to be crowned. "What nonsense all this is," said, in effect, the weighty article. "What possible good can be effected by greasing (anointing) the person of the sovereign?" And the gentle, though shallow, Macaulay prophesied utilitarianism when he spoke of ancient philosophy; of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and the rest. The leaves of this tree of ancient philosophy are beautiful indeed, Macaulay allowed. But, he asked, where is the fruit of the tree? Do Plato and Aristotle lead to the gas works and the locomotive engine? If not, what is the use of Philosophy? And, be it said in all sincerity and gravity, this utilitarian faith is by no means to be blown away with a contemptuous puff of the breath. It appeals, in one way or another, to all of us. Before we laugh at it, let us ask ourselves whether we are completely indifferent to our bodies, to our bodily comforts and discomforts, to the body's sickness and health, to its starvation or repletion. Suppose I say that I don't think that Macaulay's engine, or our motor cars and airplanes matter twopence, that it is of no real consequence whether we go fast or slow. Very fine; but my friends would tell me to walk to London and back, fifty-two miles in all, the next time I have to go in town; and then to say how I liked it. No; there is no denying that utilitarianism is a faith of universal appeal, of high cogency. There is only one thing to be said against it, and that is, that it is entirely incredible. We may be reciting the "I believe in one utility," the "Our Father Bentham," the "Hail Sewage full of chloride" and the rest: and the wind in the trees, or the glitter of the brook, or a line of Keats will scatter it all away; and we awake from nightmare, and know that the well being of the body is the means; the joys of the spirit the end. Utilitarianism, materialism are dying creeds: I shall yet see Mr. Agate on the mourners' bench of a better faith.

You can see signs of the change in all quarters and in all manners, both high and low. I hardly venture to touch on the esoteric doctrines of sciences; but it has long been evident that Prospero's exposition of the universe is far nearer to the truth of things as modern science sees it, than the science, or rather, nescience of the Tyndall, Clifford, Spencer school of the 'seventies of the last century. The very names of these people have already something obsolete about them; they will soon be utterly forgotten.

But let us not say more of these matters, which as I have confessed, are too high for me. Let us seek our signs in familiar things. Here is my instance.

Some ingenious person has invented a new cough-lozenge, a sort of medicament in which we are necessarily and perpetually interested, here in England. The benevolent inventor has called his dose (we will say) "Bung". He advertises it, and his advertisement has just caught my eye on the back page of "The Daily Mail". Here it is:

Teacher says:You observe that this eloquent appeal is in verse. Why in verse? To attract attention better. But why should a jingling verse attract attention? It certainly does. The pleasing example I have cited is one amongst many: solid men of business, great concerns, the keenest professors of the art of publicity - a word I dislike - all entreat our custom with their simple rhymes. There is the Underground Railway of London that sings:

Bung is best -

to ease the throat

and warm the chest.

Underground everywhere:And it was said that the late Lord Northcliffe, that great master of the art of advertising, paid a heavy fee to the author of:

Quickest way, cheapest fare.

Weekly DispatchIt attracts. But why does it attract? Let me ask you another. Why did Hesiod, who lived in the eighth century B.C., write his "Works and Days" in rolling hexameters? The "Works and Days" is a "Poor Richard" book, a collection of simple maxims, of unsophisticated country folk, who love to hear their own experience, their own rough-hewn common sense corroborated and condensed into a phrase. "The half is greater than the whole", says Hesiod to the man who will go to law resolved to have his claim satisfied to the uttermost, forgetful of lawyers costs. "Many things fall out between the edge of the cup and the lip", "Potter hates potter, and one craftsman another" - one sees the origins of our "There's many a slip 'twixt the cup and the lip", and "Two of a trade never agree".

Best of the Batch

But why did this remote, ancient, primitive Greek put his keen observation, his homespun wisdom into verse?

The reason is that poetry comes before prose just as singing comes before speaking. Chanted poetry is the natural utterance of primitive man; spoken prose is a later, artificial invention. All poetry was contemptible to the utilitarians, the materialists, the rationalists, the Benthamites: it was a senseless jingle, worthy, only of savages.

And now see how we return to the old way, and recommend our cough-drops with a song.

The fact is, that if we have anything of real consequence to say, we say it in poetry; and it is only natural that a man who has goods for sale should deem them of the utmost consequence.

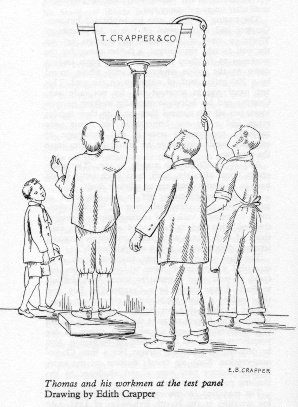

Artwork borrowed from that most revelant work Flushed With Pride - The Story of Thomas Crapper by Wallace Reyburn (Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 1971, $3.95) is by his great-niece, Edith Crapper.

Faith is not an exotic bloom to be laboriously maintained by the exclusion of most aspects of the day to day world, nor a useful delusion to be supported by sophistries and half-truths like a child's belief in Father Christmas - not, in short, a prudently unregarded adherence to a constructed creed; but rather must be, if anything, a clear-eyed recognition of the patterns and tendencies, to be found in every piece of the world's fabric, which are the lineaments of God. This is why religion can only be advice and clarification, and cannot carry any spurs of enforcement - for only belief and behavior that is independently arrived at, and then chosen, can be praised or blamed. This being the case, it can be seen as a criminal abridgement of a person's rights willfully to keep him in ignorance of any facts or opinions - no piece can be judged inadmissible, for the more stones, both bright and dark, that are added to the mosaic, the clearer is our picture of God.

The above quotation is from a speech about John Milton by Charles Taylor Coleridge, contained in The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers, published by Ace as an original paperback novel in December 1983. Perhaps some graduate student in English Literature can tell us whether Milton or Coleridge ever really said any such thing - I like it anyway, and will keep it around on this page of It Goes On The Shelf until I find something I like better as representing the proper attitude of a journalist.

This fanzine will not be sold. It will not even be distributed in the usual sense of mailing out a lot of the copies at once. This tired old fan will just send it through SFPA and Slanapa, and in trade as zines come in, and to correspondents as letters go out. If you should hear of it and feel you must have a copy, you may send a SASE for lack of anything better. If there is to be much art in future issues, I will need some good line art - no tone, no solid blacks, no shading except for dot or line - suitable for thermal stencil. I do not have to have the original, a good xerox is fine.

For those interested in the gruesome technical details, this fanzine is composed in FancyFont using WordStar on an Osborne microcomputer. It is printed on a RexRotary M4 mimeograph from stencils cut directly by the Epson MX-80 dot-matrix printer. Art is printed from thermal mimeo stencils cut by a 3M Thermofax machine.