May Ghu bless this fanzine and make it worthy at least of the

sacrifice of the trees that died to produce the paper. If you

don't like the artwork - or even if you do - send something

better, as Your Humble Editor is severely lacking in artistic

ability. Preference is for line art that will Xerox well for

thermal mimeo.

Walt Willis - Many thanks for IGOTS 1. The

circumstances of its despatch made me marvel once again at, the sheer connectivity of fandom,

but I enjoyed it too anyway. It reminded me a bit of the column I used to publish by George Charters, who also loved

odd books. I think his favourite was one by a local author who

had his novel printed at his own expense and kept the unsold

stock (about 99%) in a shed in the garden. In fact I think he

lived there too because I remember George telling me with some

awe that he had preserved all the furniture in his house by

coating it with tar. I read the novel which was queer but not

bad enough to be really memorable except, I recall that the

hero, marooned on an offshore island, was kept alive by his cat

swimming across daily with a potato in its mouth.

Harry Warner - You deserve belated thanks for the

first issue of It Goes On The Shelf. I spent most

of May watching and thinking about the climax of the

major baseball season, and only now am I

getting around to some locs that should have been written more

promptly.

The cover is effective but I'm sure I don't understand

it. The individual at the bottom looks something like Mark Twain

in old age, so maybe that's Captain Stormfield at the top

approaching a more geometrical Heaven than the one he expected

to find. Mark seems to be much in the minds of the public and

the media just now, what with his 150th birthday celebration and

his connection with Halley's Comet on its previous two passes

through this neighborhood, so maybe I'm just imagining the cover

symbolism.

Matter of fact, Mark's What Is Man? is the only extended discussion of free will I've ever read. I haven't seen the Martin Gardner book. I can agree with the belief that free will doesn't exist for the major decisions of our lives and even for some of the minor decisions. But I

find it hard to believe that social pressures and things that happened in our childhood and other external factors are responsible for every little

thing we do. Suppose I decide to get more exercise by walking around the block several times each day. Quite possibly, I

didn't make the decision to take those daily walks of my own free will. Things I've been told about good health practices,

unwillingness to walk too far from home too often in a degenerating neighborhood, the need to write lots of locs and

many other factors may have taken out of my hands the decisions about how far I would walk and how often and so on. But suppose

I also decide not of free will but from some other cause to walk on various occasions around the block in a clockwise direction

and on other occasions in a counterclockwise direction, and further, I decide that I won't choose the direction of each walk

on any systematic basis but will go one way or the other at random. Is it probable that I am not exercising free will when I

decide which way to go around to block on most of those walks?

Sometimes there may be an angry-looking dog in one direction that will decide me to start out in the other direction this

time, but most of those walks won't have any factor making one direction more advisable than the other. If I take hundreds of

those walks, I can't believe that there will be predestined reasons for my choice of direction each and every time, any

more than I believe that the position of Neptune or Mercury at the moment of my birth has anything to do with my personality

and activities as an adult.

Most of the books you describe are unknown to me. But that's not surprising, considering the number of books that

have been published in the English language and the reading time available to the average hermit. The mention in Isis Unveiled

of the therapeutic glass harmonica is strangely contradictory to the one major appearance of that musical instrument in the world

of opera. Donizetti wrote a part for a glass harmonica in the orchestral score of Lucia de Lammermoor, using it to accompany

the heroine in sections of her famous mad scene. It didn't

seem to bring Lucia to her senses. A flute almost always is used

to play the glass harmonica's part but in the Beverly Sills

recording of that opera, they found someone who could play the

glass harmonica and followed the composer's original

instructions. I have the records and I am always reminded of

movie mood music created electronically when I hear the unusual

instrument.

I was glad to have a chance to read the Machen essay.

It proves what a fine fanzine writer he would have been, if he had lived somewhat longer and read the prozine letter sections

or dropped in at a con. I'm tempted to agree whole-heartedly

with his thesis about the importance of art to civilization. But

as a practical matter, I suspect the use of poetry for

advertising purposes isn't done for aesthetic reasons

but for the utilitarian fact that words containing rhythm and

rhyme stick in the memory better than those that don't and therefore improve the effectiveness of the advertisement's method. The old legends that were communicated orally before

most people could read or write were usually in the form of poetry because this made it easier to remember them accurately.

Fortunately, Machen probably was gone before Madison Avenue made

a big thing out of its additional discovery that setting doggerel to a tune will cause it to stick even more firmly in the

listeners' minds and thus unleashed upon us the era of the

singing commercial.

You surprised me with the final paragraph. I wouldn't have guessed that you created this fanzine with computer

equipment, because it's easy to read. Most fanzines that go the

computer way become almost incompatible with my decaying vision.

((The cover was a collage of a cartoon head of

Einstein, a computer generated doo-lally, and a cartoon

version of Michelangelo's Jehovah from the Sistine Chapel.

Don't ask me what it was supposed to mean... The point of my

comments about "free will" was that it must include memory

of past events and yet not be totally predetermined by them; and

that in fact it seemed to me that consciousness and free will

must be the same thing. I didn't know about the glass

harmonica in Donezetti's Lucia de Lammermoor. Arthur

Machen could well have written to a fanzine or heard a singing

commercial, he lived until 1947. I don't know of any letters to

fanzines from him though. -nb))

Don Herron - All thanks for the unexpected It Goes

On The Shelf the 1st, which I imagine you sent on for the

Machen reprint. I can't remember exactly where I

saw the reference, & a quick look doesn't turn

it up in any indexes I have to my HPL books, but

I'm sure either HPL or Clark Ashton Smith once blurbed

Blavatsky's books as treasure troves of plot material & you can

find certain of her concepts (the succeeding races who dominate

the earth over the aeons) in their stories. Don't know, then, if

HPL had his own copy of Isis Unveiled, but I'm sure (if I can

trust my memory) that he knew of it & and had read in it a bit.

I don't think many people would last through the whole thing.

Not even fans at midnight cons.

The main reason for rushing another issue of

this zine into production right here in the middle of the January blahs is to have something to send all the nice people who sent me Christmas cards. The pages between

here and the second Arthur Machen essay will consist of

comments on the books that I acquired during the three

weeks I was in Atlanta over the holidays. A few of them

are new, and a few from used-book stores, but

most are from the junk-book corners of the various charity

places - Salvation Army, etc. Mr. Emory Bradley, who has

been a book scout in Atlanta since before the last Ice

Age, when the books were hand-lettered on parchment and

bound in mammoth-hide, knows where all these places

are - I doubt I could find them alone!

Ratings:

91-100 - Steal it if you have to!

81-90 - Worth Looking for

71-80 - Wait until it's remaindered....

61-70 - For collectors only.

51-60 - For completists only.

11-50 - Forget it!

0-10 - To read aloud in the con-suite at midnight....

- Mythago Wood, Robert Holdstock, Arbor House, New

York, 1984, $14.

- I keep hearing how great this is, but hadn't

seen a copy anywhere until I went to Mark Stevens' shop on

Highland in Atlanta. Part of it was in F&SF and Keith Roberts

liked it. As with most of the books in this issue, I haven't had

time to read it yet, so the rating is tentative.

Rating: 85

- The Illustrated Faerie Queen, Edmund Spenser,

Newsweek Books, New York, 1980, $16.95.

- A modern prose adaptation by Douglas Hill with much

beautifully printed art.

Rating: 75

- The Last Guru, Daniel Pinkwater, Bantam, New York, 1981, $1.95.

- This is currently out-of-print, but I found two

copies of it at a store in Atlanta and bought both in hopes of trading one for a Pinkwater book I don't have, such as Alan

Mendelssohn, The Boy From Mars. I have read this one and

enjoyed it a lot - not quite up to the demented standard of The

Snarkout Boys and The Avocado of Death perhaps, but a lot of

fun.

Rating: 88

- The Transmigration of Timothy Archer, Philip K.

Dick, Timescape, New York $15.50.

- This is based loosely on

the life of Bishop James Pike, it says... I am not a big PKDick fan, but the junk stores in Atlanta had dozens of these

in mint condition except for the remainder stamp on the bottom

edge so I got a couple for 50 cents.

Rating: 75

- Nostradamus and His Prophecies, Edgar Leoni, Bell,

1982.

- These silly things get bigger and fancier - this one is

823pp, claims to have all the prophecies in both French and English. Not the original 16th century French though, this is

modern French. They even include prophecies falsely attributed to Nostradamus in a separate section, and

cross-index by subject. Also a biography, personal letters, a

bibliography...

Rating: 71

- Duluth, Gore Vidal, Random House, New York, 1983.

- Looks to be a very silly book.

Rating: 55

- The Son of the Day and the Daughter of the Night,

George MacDonald, Green Tiger Press, La Jolla, 1980, illustrated by Lyn Teeple.

- Green Tiger is one of the few publishers who still make fine books in the old style. The plates

are beautifully done and tipped in on an excellent paper.

Rating: 86

- The Bat Family, Byron Preiss, Caedmon, New York,

1984.

- This is illustrated by Kenneth Smith. I can't find a

price on it. Great art and the binding looks like the

Skivertex on our Kirk book, but the paper is horribly,

blindingly white - ivory would have looked much better. Only

the dust jacket is in color, but I think Smith is at his best in

b&w anyway. The tale seems to be political satire to some

extent.

Rating: 83

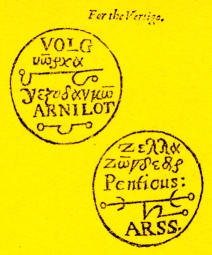

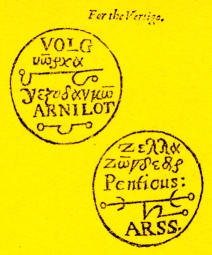

- The Archidoxes of Magic, Paracelsus, London, 1656.

- No, not an original edition, but a facsimile by Samuel Weiser (NY'75). The translation is by Robertus Turner. Was it just a con game even then, or did Turner and his contemporaries in the magic trade really believe this alchemical twaddle about links between celestial objects, various metals, and the human body? The ancient typography is fairly easy

to read. It explains how to construct the bizarre "lamens" or talismans that were supposed to

cure or protect against some malady. The example above was for vertigo, in conjunction with a potion (to be

given at 3 in the morning, the position of the planets being significant) containing 2 grains of "unicorn horn in addition to more common substances like Oil of Vitriol (what

we now call sulphuric acid) and musk (of what animal it

doesn't say).

Rating: 80

- In The Land Of Dreamy Dreams / Victory Over Japan /

The Annunciation, Ellen Gilchrist, Little-Brown, Boston,

1985.

- Two short story collections and a novel in the trade

pb editions, at $6.95, 7.95, 7.95. I had enjoyed the

author's commentary on National Public Radio's Morning Edition and

All Things Considered. These are a bit like

the work of Flannery O'Connor, a bit like the bizarre tales

of Mervyn Peake or William Sansom that lie on the fringes of

fantasy without actually having any supernatural characters or

events.

Rating: 86

- Half a Million Wild Horses, Kunigunde Duncan,

Branden, Boston, 1969.

- An "informal biography" of Julina

Boone King (1865-1920) a descendant of Daniel Boone who had a

colorful career and a dozen children - too informal for me,

the author attempts to reproduce the Texas dialect.

Rating: 60

- The Practical Princess and other Liberating Fairy

Tales, Jay Williams, Parents Magazine Press, New York, 1978.

- Excellent art, something in the style of Edmund Dulac, by

Rick Schreiter, unusually good quality color

plates. The late Jay Williams also wrote several fine mystery novels under the name

"Michael Delving".

Rating: 80

- The Golden Flash, May McNeer, Viking, New York,

1947.

- A Junior Literary Guild book about an antique fire engine, with

excellent d/w and art by Lynd Ward.

Rating: 83

- Man Made Angry, Hugh Brooke, Long & Smith, New York, 1932, $2.

- I will probably come to wonder why I bought this, but it is unusual to find

the d/w almost intact on novels this old and it isn't a common publisher. Some day I may

read enough of it to find out why Clovis Dell had two butcher knives concealed in the

bottom of his trunk...

Rating: 70

- Extra(ordinary) People, Joanna Russ, St.Martins,

New York, 1984, $4.95.

- Five stories, three of which are

reprints, one from F&SF. Looks good!

Rating: 88

- Sweetwater, Lawrence Yep, Harper & Row, New York,

1973, $3.25.

- Pictures by Julia Noonan are not bad. Obviously

fantasy, and it only cost a quarter or somesuch.

Rating: 75

- The Meaning of Liff, Douglas Adams & John Lloyd,

Harmony, New York, 1984.

- Something for my "silly book"

collection... Adams, of course, is the famous galactic

hitchhiker. This consists of odd UK place names being used in

the manner of "sniglets", new words for which there is a

supposed need in the language - "Beccles - The small bone

buttons placed in bacon sandwiches by unemployed guerrilla

dentists".

Rating: 74

- Pardon Me But You're Eating My Doily!, Robert Morley, St.Martins, New

York, 1983.

- Another silly book, a collection of "most embarrassing moments".

Rating: 72

- The Great American Misfit, William Bramhall, Potter, New York, 1982.

- Mr Bradley gave me this, an entertaining collection of historical loonies, with

excellent illustrations by the

author. The last entry is for the infamous Joe Pyne.

Rating: 82

- City of Sin, Hattie Lee Johnston, Marshall & Bruce, Nashville, nd.

- It did have a date of publication though - someone, for

whatever unimaginable reason, has erased it! Teitler

once told me that fantasy novels by women from before 1900

were extremely rare. On p.11 the heroine refers to the

"kodak clock" - anyone know what that might be? I thought

Eastman invented the word 'kodak' for his camera. The novel is a bit turgid to read, I

haven't decided yet what the fantasy content may be. It's not listed in Reginald.

Rating: 70

- The Goblin Woman, Rose O'Neill, Doubleday Doran, New York, 1930.

- With odd illustrations by the author. There

doesn't seem to be any real goblin (real goblin? What do I

mean by "real goblin"?) though. I also have Garda by this same author, who also

wrote the 'Kewpie' books.

Rating: 69

- Alimony Or Death Of The Clock, Lynn

Watson, Keegan, np, 1981.

This book seems to be on that borderline where fantasy runs off into surrealism and/or

obscurantism. No place of publication is given, but the printer was in Iowa City. There

are mystic references to Sherlock Holmes and Watson. A nicely made pb as it should be at

$7.95 for 100 pages - not that I paid that for it. I was doubtful about paying 50 cents

for it.

Rating: 10

- Carson McCullers, Lawrence Graver

Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1969.

- A mere pamphlet, but in a library binding, apparently discarded by the Atlanta Public

Library. I paid 75 cents for it mostly for the odd enclosure, which has nothing to do with

the book.

Rating: 65

Enclosed in the above book is an envelope labelled "It is not raining etc." which

contains a half sheet of paper on which is typed with a purple ribbon

the poem that starts "It is not raining rain to me/It's

raining daffodils..." with the remark that although this poem

is attributed to Robert Loveman it was actually written by a

Hindu named Swama Rama and first appeared in a magazine

called Thundering Dawn published in Lahore. The remark

is followed by the name Caroline Bensel. My 1958

Bartletts does attribute the poem to Loveman with the

title April Rain and date 1901. There is one other odd

thing about the envelope - it has a return address for an

insurance agency in Savannah printed mirror image on the

inside...

- The Utopian Thought of Restiffe de la Bretonne, Mark Poster, New York

Univ. Press, New York, l971.

- Pretty thick stuff for a non-scholar like me, but

does make the interesting remark that de la Bretonne's

1769 "Le Pornographe" was to be taken to mean "the reformer of prostitution" from the Greek

roots 'porno' and

'graphe'. Most writers give "graphe" as simply

writing so that "pornography" is "the writing of prostitutes".

Rating: 63

- Riches and fame and the pleaures of sense,

Kathy Black, Knopf, New York, 1971.

- Seldom does one find a novel from a major publisher that is worse written than Arthur

N. Scarm's The Werewolf vs. The Vampire Woman.

Rating: 9

- Revolucao No Futuro, Kurt Vonnegut,

Artenova, Rio do Janeiro, 1975.

- A Brazilian book-club (Circulo do Livro) edition of Player Piano with a prohibition

noted against selling it to anyone not in the club. Nicely made hardcover with an

illustrated binding, translation

by Roberto Mugiatti.

Rating: 62

- A Smattering Of Ignorance, Oscar Levant,

Garden City, New York, 1942.

- Who could resist that title... A funny writer in the style of the time.

Rating: 75

by Arthur Machen.

Note: See IGOTS 1 for details on the source of the following Arthur Machen essay

That Other World

So they are finding out, after all these

years, that Dickens was a considerable man. I am amused.

I knew that in 1873 or thereabouts, when I first opened the

pages that I shall never close. But, through most of my

working years, I have always been conscious of an undertone of

contempt - of kindly contempt - when Charles Dickens and his

books were mentioned. It was funny; you could hardly deny that.

But "Punch and Judy" was funny, or the children thought so.

And you would scarcely compare "Punch and Judy" with serious

drama. I did, by the way. I said that "Punch and Judy"

would outlast "Judah," a very serious drama, by Henry Arthur

Jones. And I believe that I was not far out in my prophecy. Still, that was the state of

things so far as Dickens was concerned. People were indulgent. They said: "Excellent

reading for boys"

and changed the subject to Stendahl and the "Chartreuse de

Parme." As if you were to change the subject from

Remhrandt's "Mill" to the anatomical drawing of a

louse's stomach!

Well; I gather that all this nonsense is

over, or getting over. People acknowledged to be

intellectual are writing books about Dickens. It has been

pointed out that Proust was an earnest and indefatigable student

of Dickens, that Proust discovered a deep and profound

symbolism in Dickens. And so - as I gather - there is

no more to be said. Dickens is a great man.

Am I delighted? Not vastly, I fear. I never am so much pleased as I ought to be on these

occasions. For example; I know a good dinner when I have it. A little soup, hot, and clear,

and strong: a roast fowl with a lettuce or endive salad: a dish of

spinach done with cream, or green peas cooked, not in water,

but in butter: a bit of Roquefort and a pear, or a few grapes: there, I say, is a good

dinner; and when it is despatched, both body and mind cry gratefully, Amen. And I do not

think that I am in the least gratified when Medicinæ Doctor, that well known

scientific authority, comes along and begins to babble about proteids and carbohydrates

and vitamin, and more especially about vitamins: and tells me at last that that I have

dined scientifically, even to the last fraction of an ounce: "a

perfectly balanced diet." No; I am certainly not well

pleased, not a bit of it. For the fact is; that in my heart, I don't believe that

Medicinæ Doctor knows what he's talking about; I have a suspicion that the chatter

concerning vitamins is humbug. And, furthermore, I hold a secret doctrine to the effect

that, in the last resort, all science is a lie.

A lie, that is, as a photograph is a lie; as a photograph of a landscape is a lie compared

with the picture of it that Turner painted. Science deals in information; if you would have

the truth you must go to the arts. For science is wholly of this world, but

the arts communicate in their mysterious manner the secrets of

that other world which lies beyond the vision of most

of us. It is, doubtless, for that reason that people are

willing to give enormous sums of money for the great

masterpieces of painting. They want to see the truth, and

that can only be seen through the eyes of the painter. Note

well; there is no question of likeness. Clearly, it is

beyond our power to ascertain whether Romney's sitters were like

the portraits that he painted of them. So far as I know, no

possessor of a great landscape has troubled himself to visit

the scene depicted with the purpose of verifying the

painter's accuracy. For, you cannot have a blueprint of

the light that never was on land or sea. Though, by the

way, the poet must have meant "the light that ever is on land

and sea" - if we have but the gift of vision to discern it.

Art, I say, is not chiefly concerned with likeness.

And so, after certain devious wanderings, we are back

again with Dickens. For, one of the main accusations

laid against him by the foolish is just this: that

his characters are not like anybody. That is: you and I and

Tother, and even to Totherest, are ready to affirm and

declare that we have never even been willing to say: "Though

that bald man calls himself Mortimer and wears spectacles;

yet we know him to be the veritable Wilkins Micawber." Very

good; let it be so. And what about it? Where is the law

providing that all characters in fiction must be like somebody

that we have met? Who laid this law down? I know

nothing of either law or legislator; nay, I am firmly

convinced that they do not exist: otherwise, that the

criticism of Dickens, declaring that his characters are not

"life-like," is nonsense. After all, the greatest

romance in the world is "Don Quixote" and no man ever met

or ever will meet anybody like Don Quixote. Of course we may

say of one man that he is quixotic, just as we may say of

another man that he is a perfect Micawber in his habit of

waiting for something to turn up. But note the significance

of that. By speaking in such a way, we clearly recognize the

truth that it is the absurd heroes of romance who are real.

They are the archtypes dwelling in the ineffable heaven of

the imagination; we are their more or less feeble and

confused copies. We see a man with certain qualities, and so we refer him to his

archtype, Don Quixote or Mr. Micawber. It seems

fantastic; but I believe that if these great beings had the power of uLterance as

well as of existence, it is they who would say of the rest of us: "They don't seem

very life-like." Indeed, I think we must feel, all of us, how dim and shadowy we

are compared with these

immortals; how indistinct and vague is the figure that we make

even in our own eyes. Many a man sets out in the morning

glowing with high quixotic resolutions, and slinks back at night

a sunken, sorry Sancho Panza. True to life? These figures of

Cervantes, Dickens, of the great romances are the very heart

of life, of the real life which art reveals to us.

Faith is not an exotic bloom to be laboriously maintained by the

exclusion of most aspects of the day to day world, nor a useful delusion to

be supported by sophistries and half-truths like a child's belief in Father

Christmas - not, in short, a prudently unregarded adherence to a

constructed creed; but rather must be, if anything, a clear-eyed

recognition of the patterns and tendencies, to be found in every

piece of the world's fabric, which are the lineaments of God. This is why

religion can only be advice and clarification, and cannot carry any spurs

of enforcement - for only belief and behavior that is independently arrived

at, and then chosen, can be praised or blamed. This being the case, it

can be seen as a criminal abridgement of a person's rights willfully to

keep him in ignorance of any facts or opinions - no piece can be judged

inadmissible, for the more stones, both bright and dark, that are added to

the mosaic, the clearer is our picture of God.

Milton / Coleridge / Powers

The above quotation is from a speech about John Milton by Charles Taylor

Coleridge, contained in The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers, published by

Ace as an original paperback novel in December 1983. Perhaps some graduate

student in English Literature can tell us whether Milton or Coleridge ever

really said any such thing - I like it anyway, and will keep it around on

this page of It Goes On The Shelf until I find something I like

better as representing the proper attitude of a journalist.

This fanzine will not be sold. It will not even be distributed in the usual

sense of mailing out a lot of the copies at once. This tired old fan will

just send it through SFPA and Slanapa, and in trade as zines come in, and to

correspondents as letters go out. If you should hear of it and feel you must

have a copy, you may send a SASE for lack of anything better. If there is to

be much art in future issues, I will need some good line art - no tone, no

solid blacks, no shading except for dot or line - suitable for thermal stencil.

I do not have to have the original, a good xerox is fine.

For those interested in the gruesome technical details, this fanzine is

composed in FancyFont using WordStar on an Osborne microcomputer. It

is printed on a RexRotary M4 mimeograph from stencils cut directly by the

Epson MX-80 dot-matrix printer. Art is printed from thermal mimeo stencils

cut by a 3M Thermofax machine.

Return to INDEX

Return to INDEX